Ecoss researchers co-authored IPCC Special Report on Oceans and Changing Cryosphere

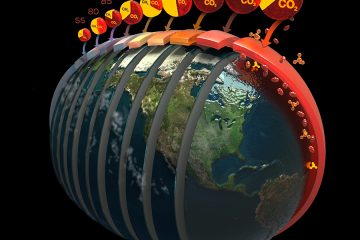

The world’s oceans are getting hotter and acidifying under climate change at unprecedented rates, threatening coastal and high-mountain communities, marine ecosystems, and global fishing stocks, according to a new Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate (SROCC) released this week by the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Ted Schuur, of the Center for Ecosystem Science and Society (Ecoss), was one of the lead authors on the report’s polar regions chapter, which synthesized research on the Arctic and Antarctic oceans, ice, glaciers, and permafrost.

Sea levels rose throughout last century, but the report found they are rising twice as fast over the last two decades, accelerated by warming temperatures, glacial and ice sheet melt, and loss of sea ice. Coastal communities around the world, including many Indigenous communities in the Arctic, are already experiencing challenges to their way of life and livelihoods, and will grow more vulnerable to more frequent flooding events and water stress.

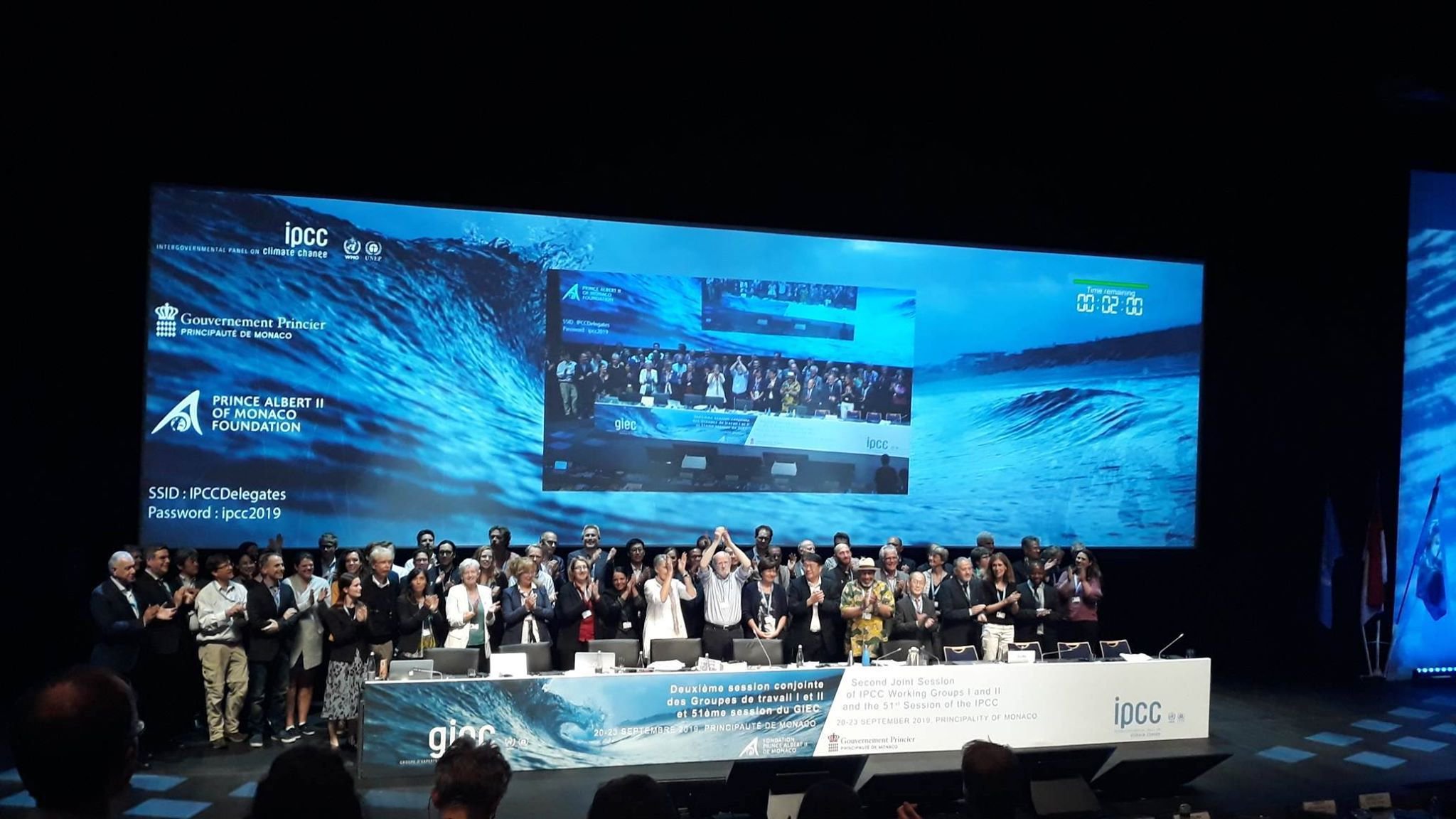

The special report, like last year’s 1.5 °C report, represents a massive and coordinated global effort: more than 100 authors from 36 countries assessed over 7000 sources that comprise the latest science on the oceans and cryosphere, or the frozen components of the earth system, including snow, glaciers, lake and sea ice, icebergs, and permafrost. Schuur met with other lead authors and government delegates last week in Monaco to approve the full report.

“It’s been rewarding to help pull together the latest science with experts from around the world,” Schuur said. “So many people on Earth depend on these two interlocked systems, oceans and cryosphere. We worked with government delegates to make sure we communicated the best and most important assessment of the current state so that communities can take action to adapt and manage risks.”

“If we reduce emissions sharply, consequences for people and their livelihoods will still be challenging, but potentially more manageable for those who are most vulnerable,” said Hoesung Lee, chair of the IPCC. “We increase our ability to build resilience and there will be more benefits for sustainable development.”

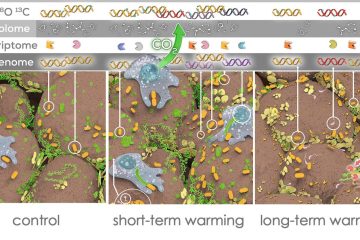

Air temperature in the Arctic is warming twice as fast as the rest of the planet, and the SROCC report authors found that even if global warming is kept well below 2 °C, a quarter of near-surface permafrost will thaw by the year 2100. In a higher-emissions scenario, nearly three quarters of that permafrost might disappear. And as it thaws, permafrost releases greenhouse gases, a dynamic that has potentially big consequences for global temperatures. This addition of greenhouse gases to the atmosphere is offset by the proliferation of carbon-capturing plants in the warming Arctic, and where this see-saw stands is critically important to designing and updating climate predictions.

Because of the remoteness of some permafrost regions and the inability to track changes in greenhouse gases there with remote sensing tools, permafrost has been harder to track as accurately and frequently as other cryosphere indicators. To do that, we need better systems to track carbon flux in permafrost regions. Schuur, SROCC contributing author Christina Schädel (Ecoss), and David Lawrence of the National Center for Atmospheric Research recently received a 4-year grant from the National Science Foundation to expand the Permafrost Carbon Network and a high-latitude carbon flux database. By inviting inputs from a global web of researchers and encouraging more synthesis, the team looks to bring permafrost carbon tracking in line with sea ice, glacial, and temperature monitoring systems.

“We can save the cryosphere,” Schuur told Science this week. “The rapidity of change sometimes leads people to think it’s too late, and it’s not.”

By Kate Petersen