Glucose addition increases the magnitude and decreases the age of soil respired carbon in a long-term permafrost incubation study

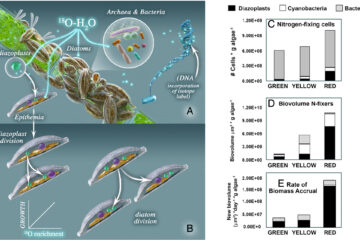

Higher temperatures in northern latitudes will increase permafrost thaw and stimulate above-and belowground plant biomass growth in tundra ecosystems. Higher plant productivity increases the input of easily decomposable carbon (C) to soil, which can stimulate microbial activity and increase soil organic matter decomposition rates. This phenomenon, known as the priming effect, is particularly interesting in permafrost because an increase in C supply to deep, previously frozen soil may accelerate decomposition of C stored for hundreds to thousands of years. The sensitivity of old permafrost C to priming is not well known; most incubation studies last less than one year, and so focus on fast-cycling C pools. Furthermore, the age of respired soil C is rarely measured, even though old C may be vulnerable to labile C inputs. We incubated soil from a moist acidic tundra site in Eight Mile Lake, Alaska for 409 days at 15 °C. Soil from surface (0–25 cm), transition (45–55 cm), and permafrost (65–85 cm) layers were amended with three pulses of uniformly 13C labeled glucose or cellulose, every 152 days. Glucose addition resulted in positive priming in the permafrost layer 7 days after each substrate addition, eliciting a two-fold increase in cumulative soil C loss relative to unamended soils with consistent effects across all three pulses. In the transition and permafrost layers, glucose addition significantly decreased the age of soil-respired CO2C with Δ14C values that were 115‰ higher. Previous field studies that measured the age of respired C in permafrost regions have attributed younger Δ14C ecosystem respiration values to higher plant contributions. However, the results from this study suggest that positive priming, due to an increase in fresh C supply to deeply thawed soil layers, can also explain the respiration of younger C observed at the ecosystem scale. We must consider priming effects to fully understand permafrost C dynamics, or we risk underestimating the contribution of soil C to ecosystem respiration.