Evolutionary history constrains microbial traits across environmental variation

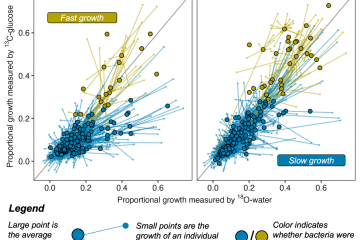

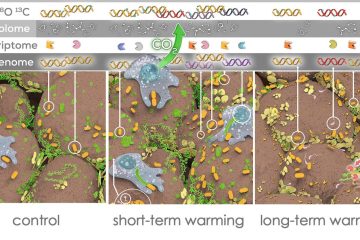

Organisms influence ecosystems, from element cycling to disturbance regimes, to trophic interactions and to energy partitioning. Microorganisms are part of this influence, and understanding their ecology in nature requires studying the traits of these organisms quantitatively in their natural habitats—a challenging task, but one which new approaches now make possible. Here, we show that growth rate and carbon assimilation rate of soil microorganisms are influenced more by evolutionary history than by climate, even across a broad climatic gradient spanning major temperate life zones, from mixed conifer forest to high-desert grassland. Most of the explained variation (~50% to ~90%) in growth rate and carbon assimilation rate was attributable to differences among taxonomic groups, indicating a strong influence of evolutionary history, and taxonomic groupings were more predictive for organisms responding to resource addition. With added carbon and nitrogen substrates, differences among taxonomic groups explained approximately eightfold more variance in growth rate than did differences in ecosystem type. Taxon-specific growth and carbon assimilation rates were highly intercorrelated across the four ecosystems, constrained by the taxonomic identity of the organisms, such that plasticity driven by environment was limited across ecosystems varying in temperature, precipitation and dominant vegetation. Taken together, our results suggest that, similar to multicellular life, the traits of prokaryotes in their natural habitats are constrained by evolutionary history to a greater degree than environmental variation.